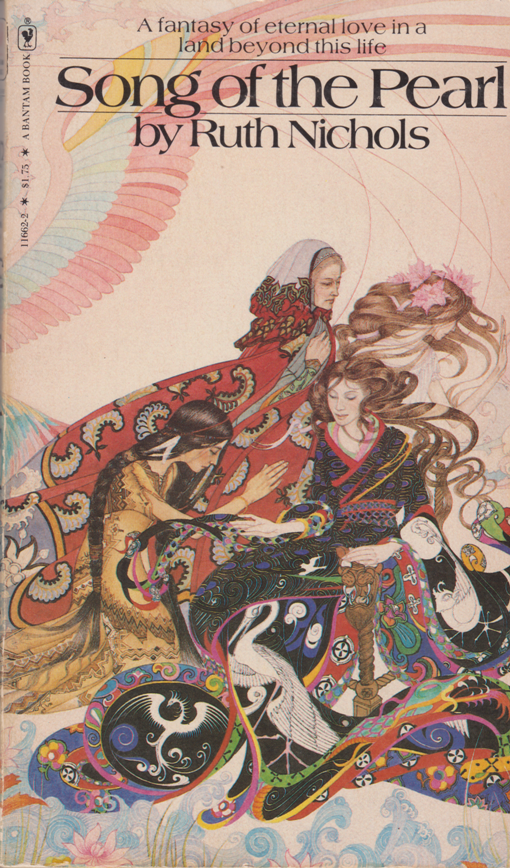

Song of the Pearl by Ruth Nichols

TW: Rape

~Quick Review~

It doesn’t matter that the writing is languid and beautiful, nor does it matter that the story is structured to appear sophisticated and nuanced, and as if it’s revealing some secret truth.

The overarching plot of Song of the Pearl perpetrates the bullshit notion that girls are to blame for the sexual attention of men. Damaging and rage-inducing at the best of times, the fact that this topic is the crux of a YA novel is unconscionable. The only pleasure I can find in this book, aside from the cover, is the knowledge that it’s out of print.

~Real Review~

The fact that this book was ever published is a testament to sexism’s existence and profound pervasiveness. If I could easily quantify the number of copies of Song of the Pearl available on the internet, I might buy them all just to prevent its message from being spread.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Song of the Pearl opens on Margaret Mary Redmond in her deathbed. Sickened with asthma and malaise of the soul, she’s given up on life. She thinks of her mother and her sisters and her father. She considers her current circumstances: how thin her arms are and how her hands look like that of a much older woman. She also thinks, in passing, of her uncle.

“Where was her uncle now? She did not know; he had gone to England; her letter to him still sat in her desk. She had never mailed it—and she was glad of that, for she knew he would have returned it unopened.”

These lines put me on edge. Feeling neurotic, I doubled back over the words, trying to figure out where I saw danger.

Maybe it was merely Margaret having a personal relationship with her uncle. Despite having more aunts and uncles than I can reasonably remember, the most I’ve ever thought of them was when I’d hide behind the couch/under the stairs during the big family Christmas party, hoping they’d forget about me and leave me to my reading.

In a healthy family (do those exist?), it wouldn’t be unreasonable for a niece and uncle to genuinely and platonically love each other, right? And maybe in that circumstance, it would be reasonable for there to be some sort of falling out that’s not completely fucked up. Right? RIGHT!?

Oh, sweet, naive, stupid me.

A bit of a disclaimer. I’m going to want to say “what the fuck?” or “well that’s fucking horrible,” or “dear cod, no, no, no, no, no. That’s not how this works, fuck all the way off,” pretty much every moment of my writing this article. I will withhold most of these comments for your sake, as they would clutter up the writing to the point of absurdity. But trust me that they’re continually snaking through my brain.

Two pages later, as Margaret’s rambling, dying thoughts continue, she reflects on an afternoon when her uncle was visiting.

Margaret, aged fourteen, heard the whispering, shuffling sound and turned on the piano stool. Her uncle flashed the [Tarot] cards at her; his smile met the blankness of her gaze. “You’ve studied Latin, Margaret?” She nodded. “Then this should give you no trouble: Qui tacet consentire.” Still she did not speak—not even to protest against the meaning, which was “Silence gives consent.”

All ambiguity is gone: her uncle is a sexual predator grooming a girl for inevitable sexual assault.

Now, I vehemently dislike this sort of topic. Still, it’s an important one—if handled correctly—and The Serpent showed me just how powerful, cathartic, and even healing properly depicting sexualized violence can be. Thus, I kept reading.

On the next page, the very next page, Margaret ruminates on how she has power, and how she uses it to enthrall and ensnare her uncle.

Now that’s a deal-breaker.

First off, it’s not set in stone that Margaret has some extraordinary gift. She seems to think she does, but it could be the delusions of youth or something that her piece of shit uncle planted in her head. It’s common for abusers to trick their victims into taking the blame for their actions.

Two pages later, after he rapes her, he says, sobbing, “Margaret, you have only yourself to blame.”

Now, this is speculative fiction, and Margaret does seem to think she has some sort of power over her uncle. In the real world, everything about this is bullshit. But maybe in this book…

I can’t even continue on this specious, sarcastic train of thought. In this fake world, it’s also bullshit because Margaret’s power, if, in fact, she even has one, seems to be mostly the power of flirting. She titillates, she entices. She doesn’t mind-control.

So even if she did somehow want this, even if she somehow straight-up forced her uncle to have sexual feelings about her, it’s still 1000000% her uncle’s fault. He’s an adult who could have cut off contact with his niece for her protection.

After the rape, her health declines. She settles into what is called “melancholia,” which exacerbates her existing health issues and ultimately causes her death.

This melancholia is not because of being raped. Oh no. It’s because Margaret feels so bad about how she tricked her uncle into raping her and how that rape only enhanced her longing for him. She feels guilty and sad and worthless and she dies.

Flames. Flames up the side of my face. Song of the Pearl is a YA novel marketed to young girls and it dares to blame a grown man’s sexual assault of a 15-year-old on the 15-year-old girl?

This book shouldn’t have been published.

Now I was in hate-read mode—I had to keep going if only to see if the book ever pulled its head out of its ass enough to realize that maybe the only person to blame for rape is the rapist.

Apparently, I’m still an optimist, though it seems I shouldn’t be.

Margaret ends up in “heaven,” which is a lot like earth except eating, drinking, and breathing are (sometimes?) optional. She’s alone and recovering from the ordeal of life and death in a beautiful little building on an island when a young man appears. He’s Chinese, he tells her to call him Paul, and he’s familiar to her, though she knows she’s never met him before. He’s kind and enigmatic and sets her on a journey before disappearing.

On this journey, she has flashbacks to previous lives.

She’s a young woman married to an unfaithful but charismatic husband while still grieving the loss of her first, and truly loved, husband. She’s cruel to her new husband, perhaps too cruel. She’s slowly dying of consumption.

She’s a girl—fifteen—and a slave. Her master fears and reveres her and rapes her. She’s pregnant and about to give birth and longing for death.

These memories of past lives are flashes, tiny vignettes, without much substance. Much more time is dedicated to her walking.

She ends up with Paul in a realistic ancient Chinese village based on, and populated by, the village where he was raised. Everyone agreed to keep their traditions and way of life alive. For example, magical baths of hot water don’t appear—no, someone must heat water over a fire and carry it, bucket by bucket, to a tub

For this purpose, they have slaves.

They have slaves. In heaven. And if a slave fucks up, one of the upper-class members of the village will carelessly hit them.

What the fuck kind of heaven is this?

As if feeling the righteous indignation of every person ever to read this book, the author gives one of the upper-class villagers a throw-away line about how the slaves volunteered to be slaves because they’re used to that life. Everyone just wanted an experience like they had on earth.

Even the slaves.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. Slaves supposedly lining up to remain enslaved even in the afterlife is right on par with Margaret supposedly tempting her uncle into raping her.

In the end, Margaret accidentally burns down the village, killing most of the villagers, and, apparently, death in heaven simply reincarnates you back to earth. You can also choose reincarnation if you tire of an afterlife that is just as stupid, or maybe even more stupid, than normal mortal life.

But Margaret and Paul survive the fire, and she remembers one more past life: she’s a young king, hounded and eventually captured by the enemy. She’s promised death by drowning in the morning, except the enemy—an older man strangely fond of this young rival king—offers her poison to spare her the worse death of drowning. She refuses his offer and calls upon a goddess to exact revenge upon this man. The goddess warns of the cost of such a request, but past-life-Margaret doesn’t care.

Present-life Margaret finally understands. Her uncle is the enemy general, the faithless second husband, the cruel but reverent master. Through her curse centuries before, she tied her fate to that of her uncle’s, that she might finally exact her revenge … except it doesn’t seem like it really worked out at all, did it? What a terrible goddess. Margaret paid the price aplenty but never got her revenge.

Anyway, Margaret feels bad and materializes to her now elderly uncle to apologize. This action breaks the curse and now, in future incarnations, she won’t be bound continuously to this man who has abused her for centuries.

She also remembers that Paul is her husband and she used to be Chinese and she loved him desperately and they plan to be reincarnated back on earth at the same time and somehow they get a glimpse into the future and know that while they won’t remember each other, they’ll still end up married in real life again.

…and will eventually end up back in heaven together where they’ll get to undergo the same ordeal of struggling to remember anything about their history before their most previous life.

Now, there are so many plot holes and questions that I could dig into, but I’ll refrain.

My big thing here is, again, that a grown man rapes a 15-year-old, and the plot of the book is getting a girl to realize that she wronged him and apologize so that she might be at peace.

I don’t care if the book makes it 100% her fault (which it doesn't), the point is that this isn’t an idea that should be pedaled to girls! Can you imagine a version of this book where a young man is molested, and the story arc is him coming to terms with his part in his being molested and APOLOGIZING TO HIS ABUSER? No. It wouldn’t happen.

I see so many glowing reviews of this book and I’m disgusted. One review even says something snarky about how parents today probably wouldn’t let their kids read it because of the adult content. Fuck that. I wouldn’t let my kid read it because it’s fucking dangerous. The rest of the world already drives the idea home that girls are to blame for the sexual attention of men. Young adult “literature” that literally preaches that point should not exist.

Of all the books I’ve read for ForFemFan, this is the first and only one I’m truly grateful is out of print. May it never find its way back to publication again.

Amusingly, while trying to track down the name of the cover artist, I stumbled across a review of Song of the Pearl in a zine published in the long-long ago. Seriously, I cannot figure out a date, but I feel like this picture dates it a bit…

Anyway, Juanita Coulson agrees with my review. Juanita Coulson also happens to be an author already on my shelf, so maybe I’ll pick her up after I’m done with my current book because if nothing else, she can really clock some bullshit.

If you feel like reveling in some past geek glory, you can find the whole edition of this Yandro zine here.

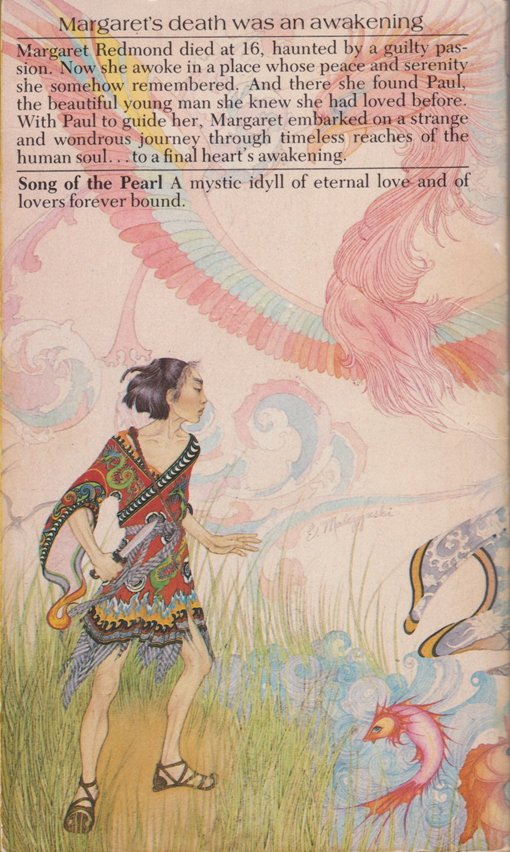

Cover art by: E. Malezyski