Tea with the Black Dragon by RA MacAvoy

3,780 Ratings | 4.01/5 Average

***Spoilers Ahead***

“A most odd and engaging fantasy.” This is how Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine described Tea with the Black Dragon. Most of the other reviews on the back of the book mirror this sentiment. “MacAvoy offers that bright and treasured rarity, a new fantasy tale,” said Locus, and the Chicago Sun-Times claimed that it was “a gem of contemporary fantasy.”

I feel like I was justified expecting Tea With The Black Dragon to be a fantasy novel.

The story starts with Martha Macnamara in a hotel restaurant, waiting for her daughter. Instead she meets Mayland Long, and they hit it off. When Martha’s daughter never shows up, Martha—with Mayland’s help—goes looking for her.

Tea with the Black Dragon is set in San Francisco in the 1980s. There is no magic. And given that plot, how can it be a fantasy? Okay, fine, Mayland used to be a dragon. Used to—as in, the magic that made him human happened off screen, long before the start of the book. I kept waiting for him to become a dragon again, or otherwise do dragon-y things, thus justifying the label of ‘fantasy.’ Aside from keen eyesight and above-average strength, though, nada. He doesn’t need to have been a dragon for this book to work.

I’ll admit that my expectation (and desire) to read a fantasy book—but then being met with an entirely different sort of book—probably did my reading of Tea With The Black Dragon no favors. I kept expecting things that didn’t happen, which got between me and the story.

That said, I love reading in general. I’m not a strictly speculative fiction kind of woman, so I could have been wooed into loving this book. And while the book has some merits, on average, I was not wooed.

Let’s start with what I didn’t like.

Mayland Long is Chinese, after a fashion. He’s a Chinese dragon, anyway, or at least claims to be. At one point his smile is described as “not Chinese, but English,” and then later, in some reversal that I don’t understand, his smile is described as “not English, but Chinese.”

Are smiles so different? Sure, a sly smile versus a mocking smile versus an ecstatic smile—those are all variations on a smile. The difference between them is clear by the adjective paired with them. How does “English” or “Chinese” qualify Mayland’s smile? The author never explains it. This leaves a sour taste in my mouth. Smiles are universal.

The line about the Chinese versus English smile isn’t so terrible, and if it were the only racially-related thing that felt ‘off,’ I’d probably not have given it second thought. But even as a white woman who isn’t finely attuned to micro-aggressions, I felt them regularly in this book.

As Mayland meets with someone, the interaction, as filtered through Martha’s POV, reads “Dr. Pecollo was a much heavier man than the Eurasian.” If Mayland weren’t Chinese (and presumed to be of mixed ancestry by Martha), that line would have read “Dr. Pecollo was a much heavier man than Mayland.”

See? Doesn’t that sound better?

Nothing about in this book feels pointedly, bigotedly racist. If anything, Mayland is put on a pedestal, but in putting him on that pedestal he’s still othered, pretty much exclusively because of his appearance and perceived ethnicity. And he's constantly othered. I wanted to throw my hands up, yell "I get it, he's Asian! Now dear cod, focus on the plot."

Or, perhaps, she ought to have focused on the story-telling.

As far as I can tell, there were roughly 10 people in the book, total. Seven of them were—if only for a moment—POV characters. Early in the story, as Martha meets Mayland, the hops between their heads are frequent and sudden enough that I had to back pedal to keep things straight. Near the end of the book, we duck into a tertiary character’s head for the span of a paragraph, then pop back out again. At a tense moment, we switch from Mayland’s POV to the antagonist’s, presumably to make Mayland’s daring attempt at escape more tense. This only lasts for a paragraph or two, and then we never see inside the antagonist’s head again.

That the book is a scant 166 pages makes these POV changes feel all the more intrusive. It was hard to feel like I got to know anyone when I never got to spend much time with them.

Another thing that crowded the book was technical jargon. As Tea With The Black Dragon revolves around the disappearance of a computer programmer, I expected—even looked forward to—absurd old/weird technology.

But Tea With The Black Dragon overdid it for me. The worst part is that it isn’t necessary for the plot, or even the setting. Neither Mayland nor Martha use computers. Computers are going to come up, but there’s no reason to dwell on them.

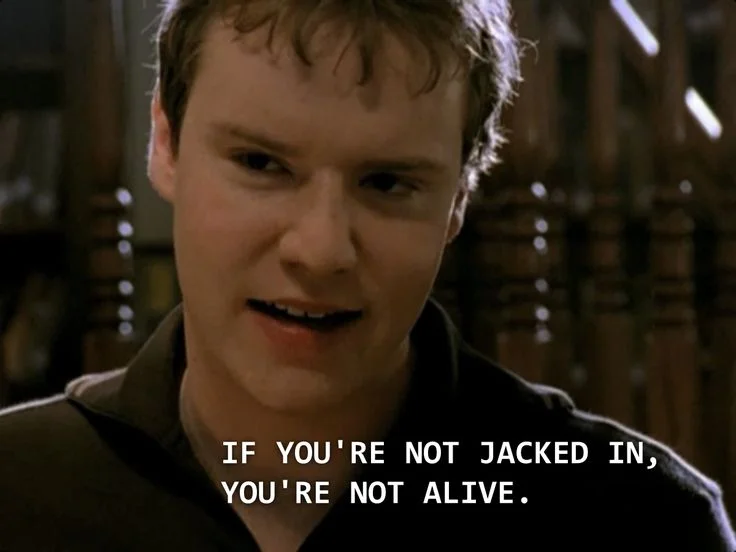

Essentially every person talking about technology in Tea with the Black Dragon is this guy.

This jargon, then, exists almost exclusively in conversation held for its own sake. It’s superfluous, confusing, and painfully dated. For example, a character says of Martha’s daughter: “just give her a handful of bipolar VLSI chips and stand back.”

Uh, okay.

Then, between jargon-heavy dialogue, we get stuck with purple prose—especially when it has to do with eyes.

“Martha’s blue china eyes shone like beads.”

Okay, okay, that’s not so bad, but they’re described this way at least a half-dozen times. Then, when I’m about ready to scream with all the mention of her damned-blue sparkling eyes, I’m treated to:

“Blue eyes and gold eyes met: two colors of flame.”

Just ugh.

And a cat gets killed in the stupidest way ever: its own owner shoots it because said owner mistakes the sound of a seven-pound cat on the floorboards for the sounds of a grown-ass man. Hell, I can tell the difference between my dogs just by listening to them walk, and there’s only a 10-pound difference between them.

But my least favorite thing about the entire book—and there’s a lot to dislike—is Martha herself. I hate to say this, but I’m going to. Martha Macnamara is a Manic Pixie Dream Girl. After a conversation where her daughter says that she’s in trouble, Martha flies to the west coast to meet her. And when her daughter doesn’t show up or call, Martha is oddly unperturbed.

When Mayland and Martha go out hunting for said daughter, Martha lets Mayland take the lead. If she had reason to think that Mayland would be a better investigator, then that would be a shrewd decision. But she doesn’t have reason to think that. And, worse than taking a back seat, Martha entirely checks out of the investigation. At one point, while Mayland is talking to a lead, Martha is playing with a remote controlled car. Afterwards, as Mayland discusses what he discovered, she blurts out that she ought to have owned a toy store.

Later, during a much more tense meeting with the same end goal, Martha is too distracted to pay attention to what Mayland and his informant are saying. Why is she distracted, you ask? She wants to know how the informant won the trophies on his shelves. Srsly.

The line that truly convinced me of her Manic Pixie state, though, is thus: “She was tired and a little depressed, so she felt it incumbent upon her to cheer up Mr. Long.”

Her daughter is missing, and she feels that she must cheer up Mayland? You can argue that it’s a coping mechanism and by cheering up/tending to Mayland she’ll distract herself from the fact that her daughter is missing ... but that feeling isn’t present in the book. After Martha tries to change the subject to more pleasant things, Mayland apologizes for having not found her daughter yet, and she goes on a tear propping him up and downplaying the severity of the fact that her daughter is missing and that all signs point to significantly foul play.

In the end, I was not surprised to find out that Martha exists almost solely as a source of inspiration for Mayland. Combine that with the fact that she does almost nothing and doesn’t affect the main plot—except in the ‘helpless maiden’ sort of way—and it’s clear: Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

Now, despite my words thus far, there were some things I rather liked:

In trying to find Martha’s daughter, Mayland makes an unexpected friend. I like this friend. There’s nothing terribly special about him—he’s not funny or particularly clever or brave. Rather, the tremendous thing about him is the perfection in which his normalcy is captured. He’s good to have in the story, and yet if he walked off the pages and into real-life, he’d seem entirely like he belonged here.

I also like that Mayland and Martha are not kids. Martha’s got a twenty-something kid herself, and Mayland looks to be in his 50s or 60s, though, as a dragon, he’s much older than that. As main characters tend to be young adults, I enjoyed this deviation from the standard.

Speaking of deviations from the norm, leading men are—sadly—normally white, and Asian men are rarely romantic leads. Mayland is a Chinese romantic lead. I very much enjoy that the author bucked expectations in this manner. It’s been over thirty years since this book was written, and this sort of representation is still a struggle.

And, despite the weirdness revolving around how he’s described, I liked Mayland. His interaction with the cat (RIP Blanco) made me want to give him a hug, and the camaraderie and loyalty between him and his unexpected friend is touching. Unlike most characters chasing their Manic Pixie Dream Partner, I never felt like Mayland put the onus of himself on Martha’s shoulders. His involvement with her isn’t entirely honorable—he mostly offers to help look into the daughter’s disappearance because he’s afraid of losing contact with Martha—but also at no point does he lay his pieces before Martha and ask her to fix him. The satisfaction and sense of completion he gets from Martha, he gets without overburdening her, or, well, burdening her at all. He’s a good guy. Now, if he only weren’t convinced he needed Martha to complete him.

I didn’t love this book, but, well, I did finish it. I was mostly curious if and how it would turn into a fantasy, and I did want to see what Mayland got up to. I do think I would have liked it more had I gone into it expecting it to be a light romance-thriller with dashes of mystery, which, were I asked to label this baby with a genre, is what I would have come up with.

I think Tea with the Black Dragon is the sort of book that would lend itself to younger women. At thirty, the idea of a man looking to a woman to complete him doesn’t seem even remotely romantic. At twenty, I suspect I would have felt very differently.

Timing also probably matters. In 1983 Tea With The Black Dragon might have felt fresh and different, but shape-shifting erotica is pretty much a genre unto itself at this point. One shape-shifter, who no longer shifts, does little to intrigue me. Especially when the plot isn’t impacted by his post-shape-shifter status.

So I can understand all the glowing reviews online, most of which were written by folks who first read the book decades ago, but, well, I don’t share them. This is book number two of ForFemFan that I give a thumbs down.

Cover art by Pauline Ellison